Concerning the Spiritual in Music

Palestrina’s Kyrie from 1567

The Ends of Music

Music is an exercise that incorporates the physical and intellectual abilities of the performer in a spiritual act. The art we create in this physical realm transcends our material existence by communicating a spiritual message. In the words of Kandinsky, we “sought for the ‘inner’ by way of the ‘outer’” (1). I am not alone in this view. This spiritual view of music has been explicitly stated over the past three millennia.

“Sing to the Lord a new song, for He has done marvelous things”

— Psalm 98 verse 1

“Musical training is a more potent instrument than any other, because rhythm and harmony find their way into the inward places of the soul.”

Thomas Aquinas is one of my favorite philosophers. An important aspect of his work was reconciling Aristotelian philosophy with the revealed truths of Christianity.

— Plato (15)

“music has the power of producing a certain effect on the moral character of the soul, and if it has the power to do this, it is clear that the young must be directed to music and must be educated in it. Also, education in music is well adapted to the youthful nature; for the young owing to their youth cannot endure anything not sweetened by pleasure, and music is by nature a thing that has a pleasant sweetness.”

— Aristotle (16)

“Music is the exaltation of the mind derived from things eternal, bursting forth in sound.”

— Saint Thomas Aquinas (2)

“The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is mov’d with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils;

The motions of his spirit are dull as night,

And his affections dark as Erebus:

Let no such man be trusted. Mark the music.”

— Shakespeare (3)

“Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy. Music is the electrical soil in which the spirit lives, thinks and invents.”

— Ludwig Van Beethoven

“music has been for some centuries the art which has devoted itself not to the reproduction of natural phenomena, but rather to the expression of the artist’s soul, in musical sound.”

— Wassily Kandinsky (1)

“And they sang a new song before the throne and before the four living creatures and the elders. No one could learn the song except the 144,000 who had been redeemed from the earth.”

-- The Book of Revelation: Chapter 14, verse 3

Christianity and Western Civilization

St. Benedict is known as the father of Western Monasticism. He wrote the “Rule of St. Benedict.” Communities of Benedictine monks still live by this rule today.

It is no secret that our great western democracies are cultural heirs of the classical Greek and Roman civilizations. What is less well known however, is that unlike the bronze age collapse of the 11th or 12th century BC, the knowledge and traditions of the classical era were preserved and built upon by the Christian faith -- especially as lived out by Benedictine Monks. (5) To take just one example, literacy, something we take for granted today, and something that completely died out in large areas of the Mediterranean and Middle East after the Bronze age collapse (6), was kept alive by monks in Western Europe after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. (7) GK Chesterton eloquently described this in his book “Orthodoxy”:

"I found that Christianity, so far from belonging to the dark ages, was the one path across the dark ages that was not dark. It was a shining bridge connecting two shining civilisations.” (8)

Monumental musical innovations occurred during the so-called “dark ages” and renaissance. This included staff notation, counterpoint, polyphony, equal temperament, and many of the instruments we still use today (Strings, brass, woodwinds, organ, harpsichord, etc). Specific Gregorian chants like Dies Irae (from the 13th century) continue to be used by composers like Hector Berlioz, Benjamin Britten, and even John Williams.

The Sacraments — A material portal to the transcendent

“A Sacrament is an outward sign of inner grace”

-- Saint Augustine (17)

I wanted to include a quote from John Henry Newman because the Catholic teaching on the sacraments played a significant role in his conversion from the Church of England. James Joyce once said, “Nobody has written English that can be compared with Newman's cloistered silver veined prose.”

“The sacraments are efficacious signs of grace”

-- Catechism of the Catholic Church (18)

For the reasons listed above, it is important to look at how the Catholic faith has shaped western culture. Christianity is an incarnational religion. As C. S. Lewis put it, “The Son of God became man to enable men to become the sons of God.” (9) This idea around the importance of God existing in our own material world may be better understood by contrasting it with some of the Stoic views that preceded it. Epictetus said “You are a little soul carrying about a corpse.” In describing how Christian views differ from Stoicism (although they do overlap in certain areas), Charles Taylor points out that if our material existence is perceived to be meaningless, then Christ’s sacrifice is also meaningless. (10)

This idea of God himself being present not just spiritually, but also physically in our day to day lives is shown in the celebration of Christ’s sacrifice at every mass. This is not a mere token of remembrance. Catholics believe the bread and wine is “transubstantiated” (transformed) into the body and blood of Jesus. St. Francis of Assisi said, “What wonderful majesty! What stupendous condescension! O sublime humility! That the Lord of the whole universe, God and the Son of God, should humble Himself like this under the form of a little bread, for our salvation.” More recently (in the 20th Century), St. Maximillian Kolbe said, “God dwells in our midst, in the Blessed Sacrament of the altar.”

This view on transubstantiation was radically changed in western culture with the advent of Calvinism in the 16th century. Jean Calvin explicitly rejected the dogma of transubstantiation:

“we conclude, without doubt, that this transubstantiation is an invention forged by the devil to corrupt the true nature of the Supper.” (11)

The recently canonized John Henry Newman — a convert from protestantism — keenly felt the real presence of Jesus when he said this in the 19th century:

“A cloud of incense was rising on high; the people suddenly all bowed low; what could it mean? The truth flashed on him, fearfully yet sweetly; it was the Blessed Sacrament - it was the Lord Incarnate who was on the altar, who had come to visit and bless his people. It was the Great Presence, which makes a Catholic Church different from every other place in the world; which makes it, as no other place can be - holy.”

Because of this change in dogma around the sacraments, the public and communal practices of faith typical of Medieval Christianity were replaced by the hyper-Augustinian (dualistic) tendencies that found a foothold after having previously been repressed in the 13th century. (12) The interiorization of acts of faith had effects far beyond the wars of religion that would rage over the next two centuries. As Taylor details, pulling God out of our material world meant we only see him in ourselves. (10) This would directly lead to the rise of “exclusive humanism.”

So far, I’ve discussed the importance of Catholicism in preserving and building upon prior civilization (classical Greece and Rome). I’ve touched on the metaphysics of Catholic vs. Protestant belief, and (without getting into a theological debate) shown how these differing beliefs affect how they view the world, but how does this effect art, or more specifically music?

Michelangelo’s Pietà. I was fortunate to see this in person at St. Peter’s in Rome. The Pietà is a common subject in Christian art. For example, I saw a similar sculpture in wood when I visited the De Krijtberg Catholic Church in Amsterdam.

Renaissance and Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm: this example is from the Cathedral of St. Martin in Utrecht

The clearest historical example of how these belief systems are enacted is the stark contrast between the contemporaneous events of the Renaissance in Southern Europe, and the Iconoclasm in Northern Europe culminating in the Beeldenstorm (also known as “the Great Iconoclasm”) in 1566. The Renaissance had Michelangelo and Palestrina working in Rome: Michelangelo on sculpture (e.g. the Pieta) and painting (e.g. the Sistine Chapel); Palestrina on musical innovations to counterpoint and polyphony. In Spain, El Greco was pioneering expressionism. In Venice, Monteverdi (who was a priest) developed new musical styles like Opera and Basso Continuo. These musical works are still performed worldwide, and this art is still viewed by many from across the globe. Simultaneously in Northern Europe, art had not just been pushed to the margins of society, it was being decried as idolatry and actively destroyed by nobles and commoners alike across Scotland, England, and the Low Countries explicitly in the name of Jean Calvin’s teachings. During my visit to the Netherlands, I was fortunate to see some of the precious little art that survived the destruction of the Calvinists.

In the same treatise in which Calvin rejects Transubstantiation, Calvin states:

"they will despise and condemn as idolatrous all those superstitious practices of carrying about the sacrament in pomp and procession, and building tabernacles in which to adore it.” (11)

— Jean Calvin (emphasis mine)

A tabernacle is the vessel in which the Eucharist is contained. A church is built to house the tabernacle. It is important to note that traditionally, Cathedrals are built in the shape of a cross, and the tabernacle is in the center. Beautiful Churches like Notre Dame that had graced the European countryside for centuries leading up to Calvin were not just thought unnecessary, they were idolatrous. Calvin and his followers also banned musical instruments:

“The Papacy was guilty of foolish and ridiculous imitation when it decorated churches and thought to offer God a more worthy service by employing organs and other follies of that sort. By these the Word and worship of God are profaned, for the people interest themselves in these things more than in the Divine Word. Where there is no intelligence there is no edification . . . That which was useful under the Law has no place under the Gospel, and we must abstain from such things not only as superfluous, but as frivolous. All that is needed in the praise of God is a pure and simple modulation of the voice. Instrumental music was tolerated because of the condition of the people. They were, Scripture tells us, children who used childish toys which must be put away if we wish not to destroy evangelical perfection”

— John Calvin’s 66th Homily on 1 Samuel, chapter 18

…He even melted down a pipe organ to be made into cups. (13)

With this historical context, we can see that the art-valuing world informed by Catholic belief in transubstantiation and the sacraments is a far cry from the Calvinist view that beauty in art or music is idolatry. This Calvinist view would be brought to America at the beginning of the 17th century.

Coming to America

From Plymouth Rock, to the celebrations of “Pope night,” to the Old South Meeting House (14), to the “blue laws” that still exist in certain states, America is an inheritor not just of the Greco-Roman tradition the Founders looked to when writing the Constitution, but also the Calvinist creed brought by the Puritans.

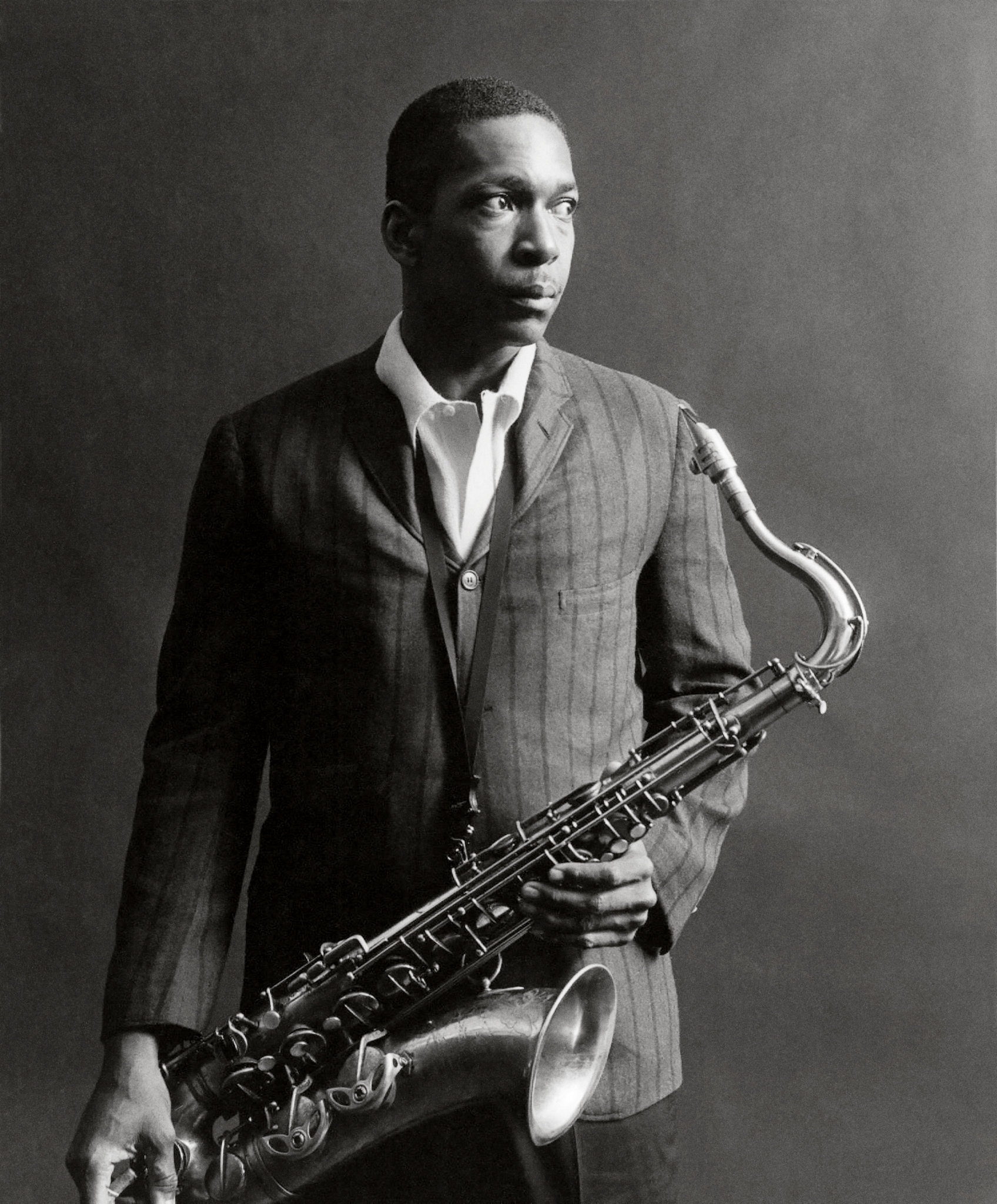

John Coltrane is one of my favorite musicians. His music is powerfully spiritual.

This leaves Americans at a curious cultural crossroads. From today’s Calvinists that added instruments back into their services, to the “exclusive humanists” who spend vast sums of money to attend stadium concerts, the orchestra, or a broadway musical; everyone feels the spiritual power of music. Because today’s dominant cultural narratives of Dualism and Humanism lack a coherent explanation for the spiritual experience felt by all, we live in a confused culture where John Coltrane’s music can be listened to by millions across the world while his historic house here in Philadelphia falls into ruin, only to be noticed by a simple blue sign in front of a trash-strewn sidewalk.

Time permitting, I hope to dig deeper into this “exclusive humanism” and how it evolved from the Protestant reformation. I will give examples of this push for “exclusive humanism” from arts institutions, academia, primary and secondary schools, NAfME, and others. Hopefully that could be a starting point for discussion on how to reconcile these two conflicting views on the arts.

For now, I’ll leave off on a positive note with two quotes from the 20th century; one from Kandinsky and one from John Coltrane. First the Kandinsky:

“In real art theory does not precede practice, but follows her. Everything is, at first, a matter of feeling” (1)

As long as there is passion and feeling around the arts, I have faith that people can regain a coherent idea around what the arts are, their function, and why they should be taught.

And lastly, Coltrane:

“music is a way of giving thanks to God.” (4)

Kandinsky, Wassily, and M. T. H. Sadler. Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Dover Publications, 1977.

Aquinas, Thomas, and Timothy Lachlan. Suttor. Summa Theologiae. Blackfriars, 1970.

Shakespeare, William, et al. The Merchant of Venice. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

DeVito, Chris, and John Coltrane. Coltrane on Coltrane: the John Coltrane Interviews. Chicago Review Press, 2012.

The Rule of St. Benedict in English. Liturgical Press, 2016.

Cline, Eric H. 1177 BC: The year civilization collapsed. Princeton University Press, 2015.

Woods Jr, Thomas. How the Catholic Church built western civilization. Regnery Publishing, 2012.

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. Orthodoxy. Vol. 12. Image, 2012.

Lewis, Clive Staples. Mere christianity. Zondervan, 2001.

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Harvard university press, 2007.

Calvin, John. "Short Treatise on the Supper of our Lord." Selected Works of Calvin 2: 168.

Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. Saint Thomas of Aquinas. Vol. 36. Image, 1956.

Reyburn, Hugh Young. John Calvin: His life, letters, and work. Hodder and Stoughton, 1914.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution. Random House, 2013.

Bloom, Allan, and Adam Kirsch. The republic of Plato. Basic Books, 2016.

Barker, Ernest, and R. F. Stalley. "Aristotle: Politics." (1946).

Augustine, Saint. The first catechetical instruction: De catechizandis rudibus. Vol. 2. The Newman Bookshop, 1946.

Paul II, Pope John. Catechism of the Catholic church. London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1994.